“You wind up continually pondering what goes on in their minds.” Hecht, who joined the personnel in January, has distributed her first paper on our canine confidants in the Journal of Neuroscience, finding that various varieties have distinctive cerebrum associations inferable from human development of explicit traits.

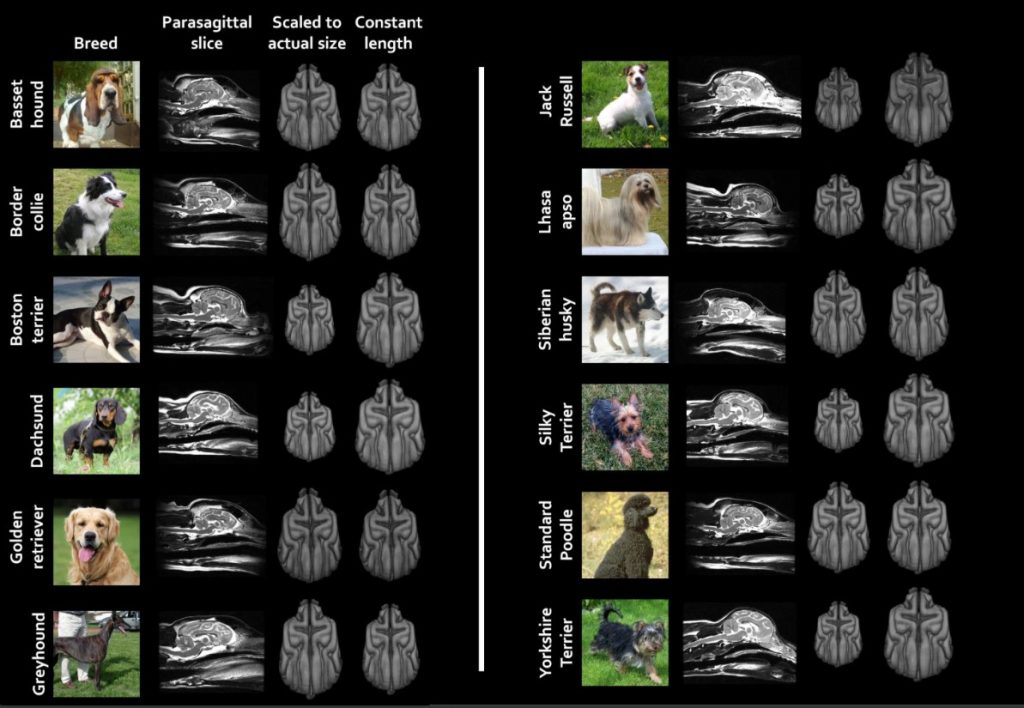

Erin Hecht, talking as both researcher and pooch sweetheart, clarified how her inclinations met up: “They ask to be investigated,” said the associate teacher of neuroscience in the division of Human Evolutionary Biology. Using MRI checks from 63 mutts of 33 varieties, Hecht discovered neuroanatomical highlights relating to various practices, for example, chasing, guarding, crowding, and friendship.

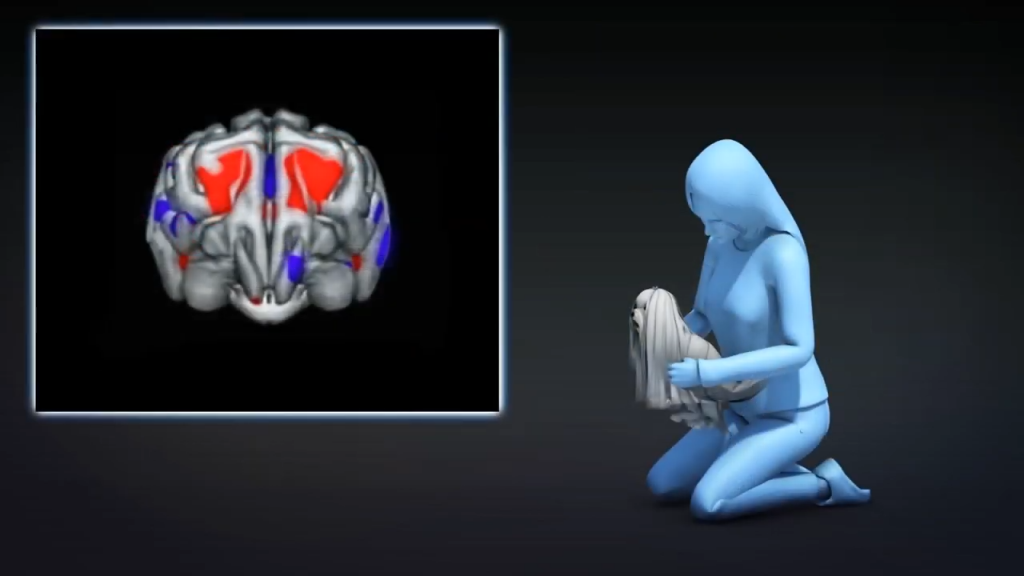

Sight chasing and recovering, for instance, were both attached to a system that included districts associated with vision, eye development, and spatial route. “In my profession up until this point, there have been a few times when you take a gander at the crude pictures and know there is something there even before you do measurements. This was one of these occasions,” she said.

“I resembled ‘Sacred dairy animals! Why nobody else has done this?'” Hecht isn’t altogether certain why canines have not been for some time considered appropriate examination subjects, yet she hypothesizes that it’s anything but difficult to excuse what lies at your feet. “It was abnormal to do this in 2012. At the point when I told individuals, some would state, ‘Goodness that is adorable,'” she said. “It required some investment to persuade different researchers and financing offices that pooches could truly disclose to us something about cerebrum evolution.

“Hecht came to examining hounds by method of a side venture while in graduate school at Emory University considering human mind development. Seven years prior, she ended up viewing a nature appear about local mutts and specifically reared Russian foxes.

The researcher examining the mutts and foxes talked about hereditary qualities and development, however there was no notice of neuroscience. “I thought, ‘How is this conceivable? Nobody’s idea about taking a gander at their cerebrums,'” Hecht reviewed. She connected with Lyudmila Trut at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics (some portion of the Russian Academy of Sciences) in Siberia.

Trut associated her with scientists chipping away at tamed foxes, who gave her about six minds for a pilot study. Around a similar time, Hecht discovered Marc Kent, a veterinary nervous system specialist at University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, who shared many MRI outputs of his four-legged patients. “I had this informational index and felt fortunate I approached it,” she said. “Following a few years, the [National Science Foundation] financed the investigation to keep examining hounds and these foxes.” Sitting in her office over the Museum of Comparative Zoology, flanked by her own Australian shepherds, Lefty and Izzy, Hecht said she and her associates had the option see that the variety contrasts weren’t haphazardly circulated, yet were, truth be told, centered in specific pieces of the mind.

They inspected fluctuation, pinpointing six systems of the cerebrum where life structures related with kinds of preparing significant for various varieties: reward, olfaction, eye development, social activity and higher perception, dread and tension, and aroma handling and vision. There were a few astonishments. For instance, expertise in chasing by aroma was not related with the life structures of the olfactory bulb. “Or maybe, this aptitude was connected to higher-request locales that are associated with progressively complex parts of fragrance handling,” she said.

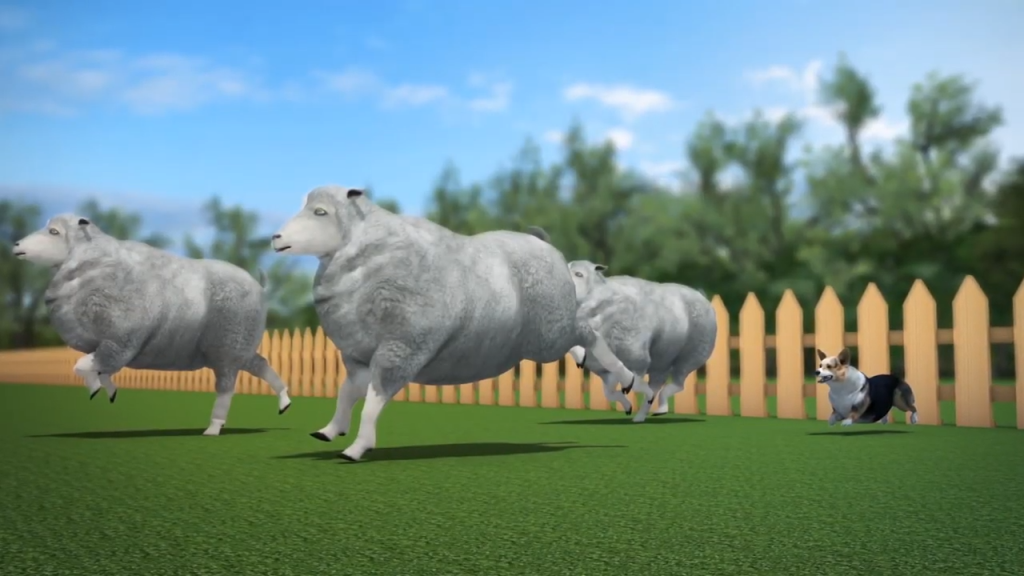

“It’s not tied in with having a cerebrum that can distinguish if the fragrance is there. It’s tied in with having the neural hardware to choose how to manage that data.” Hecht’s lab additionally considers cerebrum advancement in people, yet she said proceeding with the pooch look into gives a window into understanding the human mind.”Border collies are stunning at crowding, however they aren’t brought into the world realizing how to group. They must be presented to sheep; there is some preparation included. Learning assumes a critical job, yet there’s plainly something about crowding that is as of now in their minds when they are conceived. It’s not inborn conduct, it’s an inclination to discover that conduct.

That is similar to what goes on with people with language. They don’t jump out of the belly having the option to talk, however obviously all people are inclined in a critical manner to learn language. On the off chance that we can make sense of how advancement got those abilities into hound cerebrums, it may assist us with seeing how people developed the aptitudes that different us from different creatures,” she said. With that in mind, Hecht is presently reading hounds explicitly reproduced for execution. With the assistance of Sophie Barton, a Ph.D. up-and-comer in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the lab is presently selecting various working canine varieties, including profoundly gifted German shepherds occupied with schutzhund (military dutifulness) preparing, fringe collies who contend in crowding rivalries, retrievers who exceed expectations at field preliminaries, and that’s only the tip of the iceberg.

They are contemplating both boss mutts and their low-ability littermates. “We’re looking for animals raised in the same environment where, for whatever reason, one has excelled and one dropped out,” she said. That will give researchers a better sense of how recent evolution of dog brains shaped the anatomy inherited from their ancestors, even if it’s “an evolutionary eyeblink.” And, as for the question she gets asked most — “What’s the smartest dog?” — Hecht has the science to back up her diplomatic answer. “This research suggests there’s not one type of canine intelligence,” she said. “There are multiple types.” Another story in video: